From the Ground Up: The AT’s Overlooked History

By Meg Drennan

“I took my first hike in 1971 in Shenandoah as a Boy Scout. Our Scout Master had been a marine in WWII. He believed you developed self-reliance by getting out into the woods, backpacking, and walking on the trail,” recalls Mills Kelly.

Back then, they didn’t think much about the Appalachian Trail (AT). It was just the place where the troop hiked.

“Two years later, a neighbor came to our Scout meeting and gave a slide show of his thru-hike. I remember thinking, the trail is 2,000 miles long? It goes from Georgia to Maine? That’s how my fascination began at age 12.”

Since then, he’s hiked more than 800 miles of the AT over the years. As the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club’s (PATC) archivist, Kelly has explored many more miles by sifting through the written narratives, photos, recipes and other artifacts left behind by hikers of yore.

An emeritus professor of history at George Mason University, Kelly is fascinated by the accounts from casual day hikers. But their stories are largely tucked away, stored in ledgers, boxes and archives by various clubs up and down the AT.

By contrast, he says, thru-hikers are celebrities of sorts. “They’ve published books. They’ve got YouTube videos, social media posts. But they are only one half of one percent of all the people who get on the trail each year.”

What about everyone else? “I’ve tried to impress on my students to beware of the preponderance of evidence fallacy. There may be a ton of evidence about one part of story, but not much about the other. The AT is a case study in this. It was really bugging me.”

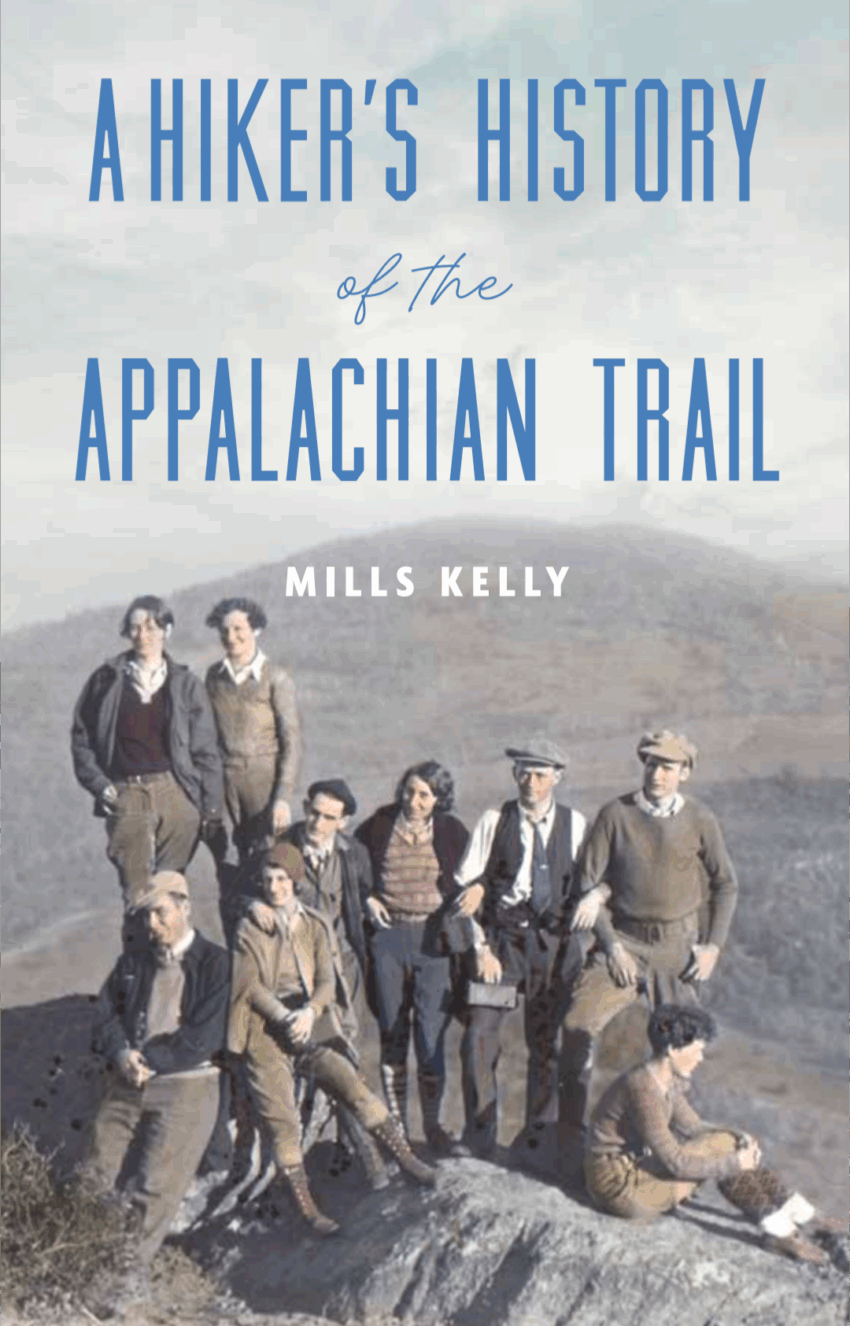

So, he decided to write a book. In A Hiker's History of the Appalachian Trail, Mills captures the experiences of those everyday AT hikers over the past century. To tell their stories, he dug through hundreds of trail shelter registers, hiker accounts, old photos and films, and newspaper and magazine articles.

“I was a Fulbright in Germany last year. When I wasn’t teaching, I spent my time reading those accounts. I have to give a big shoutout to the people at the AT museum in Pine Grove Furnace, PA. They’ve been scanning their ledgers and gave me a thumb drive filled with those scans.” As he read and absorbed those personal narratives, several themes emerged.

“In 1921, Benton MacKaye wanted people to go on the trail to get oxygen, peace, just after flu epidemic and the war. He thought the trail would be a place for people ‘to solve the problem of living.’ Turns out, he was right! People ventured onto the AT to touch the wild. They wanted to see a wild animal, sit by a stream and listen to the water rushing over stones, or see wildflowers. They wanted what the Japanese call komorebi, light filtering through the leaves.”

They still do. Every year, between 3 to 4 million people hit the trail.

“What doesn’t change over time is this desire to touch the wild. What does change is who you do it with. Until the early 1960s, you hiked in a group. You joined a club, scouts, a church group. There are lots of photos of 20, 30, even 40 people. At the end of hikes, they would square dance.”

Back then, socializing was a big part of hiking. “We assume from our lens of the 21st century that women’s participation in hiking was not the norm. That’s wrong. Women have been doing long distance, rigorous hiking from the beginning. Some hiking clubs even had a 50/50 men and women limit because there were too many women. It was an important social outlet. A place where you might meet your life partner.”

Group hiking, however, started to decline in the 1960s when Americans shifted to individual activities, like jogging and aerobics. Today, he notes, backpackers increasingly hike by themselves.

“It has a big impact on what happens on the trail. Hikers used to create, support, and maintain the trail as a group. When they are solo, they become consumers of the trail. Thru hikers are consumers. Almost none of them volunteer.” Other changes have been more welcome.

“Onion sandwiches used to be very popular for decades. Also, big slabs of raw bacon,” he laughs. “I enjoyed researching the evolution of the gear we carry. World War II spurred tremendous innovation in camping and hiking gear. The hammock tents, popular today, came from the Pacific campaign. These innovations led to much lighter, more durable gear that made the backcountry accessible to many more people.”

Kelly’s new book will be available for purchase on October 7th. Join Mills in person for a book launch at Blacksburg Books on October 9th. For more information or to pre-order the book, visit millskelly.net. And be sure to check out his podcast, The Green Tunnel.